How Switzerland's Famous Dairy Cow Bells are Made

A dairy cow wearing a traditional Swiss bell. By Christina Holmes

Inside the workshop of a Swiss family bellmaker.

In the pastures outside of Fribourg, Switzerland, gently undulating fields of green rise up to meet pure blue sky at the horizon. Rugged mountains reach upward, craggy peaks white with snow. As far as the eye can see, huge dairy cows with their black-and-chestnut-colored markings dot the fields. Standing nearly 5 feet tall and weighing up to 2,000 pounds, these gentle giants lazily graze on lush grass and wildflowers. Their resulting milk—harvested twice a day—is transformed into some of the world’s greatest dairy: Dense and nutty Gruyère AOP cheese comes from the canton of Fribourg, as does thick double cream and exquisite milky-sweet butter.

Hanging from each cow’s massive neck is one of the most recognizable symbols of Swiss farming culture: the Treichel. The northern German-Swiss farmers call it a Kuhglocke. Others simply know it as a cowbell. Though they are frequently seen as decorations for animals in regional festivals such as Desalpe—the fall celebration during which Alpine animals are led from the mountains to the prairies for the winter—the bells have served an important role in livestock management for more than 900 years.

A bell’s size and timbre convey information about the animal wearing it. Dominant alpha animals—the highest ranking male or female in the group—wear the largest bells. The deeper and louder tones are an audible beacon for the others in the herd to follow. Juveniles wear much smaller bells, the higher pitch making it easier to locate a stray. Bell size also might convey a farmer’s pride in a particular animal. A favorite cow will often sport a large bell attached to a thick strap ornately decorated with significant dates or depictions of the farmer’s family events.

Twenty-five miles north of the quiet pastures and idyllic landscapes is the small Fribourg suburb of Villars-sur-Glâne. In a small building, bell-maker Stéphane Brügger has long created many of the bells heard across the country. He has been a fabricant des cloches for more than 31 years—most of his adult life. He is second generation, having learned the trade from his father. “He taught me the basics, then practice took care of the rest,” he says.

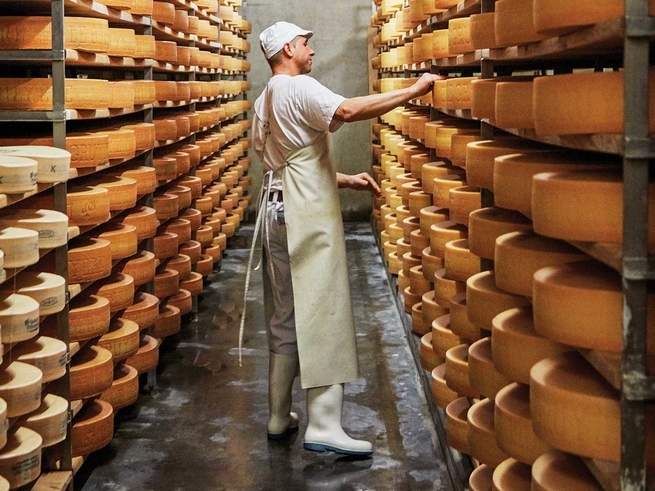

Wheels of Grùyere age in a cellar in the village of Rueyres-Treyfayes. By Christina Holmes

Brügger’s smelting workshop is dark and sooty, except for a small office and customer area kept neat and tidy. Heavy wrought-iron tools, blackened forging ovens, and worn bell molds take up most of the space. Shelving holds his current inventory of finished bells, usually numbering around 30.

Making bells by hand is arduous and dirty work, and it can take hours or days, depending on the size and complexity of a bell’s design. Using a steel template, Brügger cuts the halves, then hand-engraves and details them. He heats the metal and contours it using a forging press, then hammers the pieces into just the right shape. After welding the bell and adding a handle and ringing hammer, he grinds it to a smooth finish. An optional dip in hydrochloric acid removes any dark spotting remaining from the welding before a final drying and polishing.

Brügger’s youngest son, Arnaud, has expressed an interest in the craft and works at Brügger’s side, a third generation learning the ropes, but his older son chose to pursue engineering. Given the long hours and long-term uncertainty that comes with being a bell-maker, he understands both decisions. “They were free to make their own choices,” Brügger says. “I told them the key is to do what you love.”